Chicago, a city renowned for its architecture, its history, and its vibrant culture, is also celebrated for its remarkably logical and navigable street grid. Unlike many older American cities that evolved organically, Chicago’s street layout was born from a deliberate plan, a testament to the city’s rapid growth and forward-thinking vision. This article will delve into the intricacies of Chicago’s street map, exploring its origins, its unique features, and the stories it tells about the city’s development.

The Burnham Plan and the Rectilinear Grid: Foundations of Order

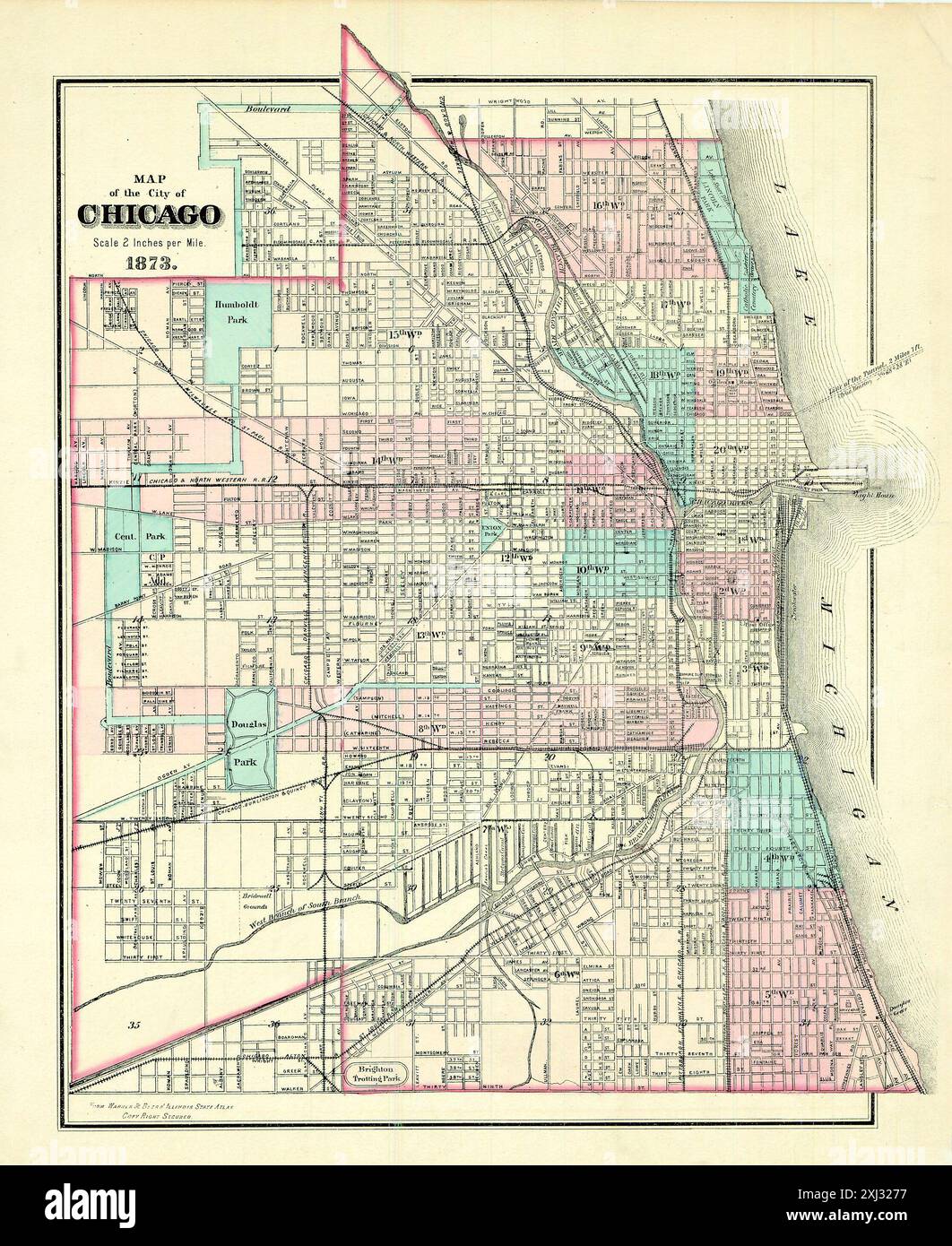

While the seeds of Chicago’s grid were sown before, the pivotal moment in shaping its streetscape came with the Burnham Plan of 1909. Officially titled "Plan of Chicago," this ambitious urban planning document, co-authored by architect Daniel Burnham and planner Edward Bennett, envisioned a grand, modern city. While the plan encompassed much more than just streets, its proposals for a rationalized transportation system, including a standardized street grid, were foundational.

The Burnham Plan advocated for a rectilinear grid, a system of streets intersecting at right angles, providing a highly organized and predictable layout. This contrasted sharply with the often-convoluted street patterns of cities that had grown haphazardly. The grid was intended to facilitate efficient transportation, encourage commerce, and promote orderly development.

The Numbering System: A Masterclass in Logic

Perhaps the most distinctive and user-friendly aspect of Chicago’s street map is its coherent numbering system. This system, based on the point of origin at State and Madison Streets in the heart of downtown, provides a logical framework for finding any address within the city.

-

State Street: Divides the city into east and west. Addresses increase in either direction away from State Street. So, 100 West Madison, for example, is one block west of State Street, while 100 East Madison is one block east.

-

Madison Street: Divides the city into north and south. Addresses increase in either direction away from Madison Street. Consequently, 100 North State is one block north of Madison, while 100 South State is one block south.

-

The Block System: Every 100 numbers represents one block. This consistent spacing allows for easy estimation of distances. Knowing that 400 North is four blocks north of Madison, for instance, allows you to quickly gauge your position.

-

Avenues and Streets: Avenues generally run north-south, while streets run east-west. This convention further simplifies navigation.

This system, while requiring some initial understanding, quickly becomes intuitive. Residents and visitors alike can easily navigate the city with minimal reliance on GPS, a testament to the system’s effectiveness.

Exceptions to the Rule: Deviations and Diagonal Streets

While the grid dominates, Chicago’s street map isn’t entirely devoid of exceptions. The most prominent of these are the diagonal streets, which often follow former Native American trails or early transportation routes.

-

Milwaukee Avenue: This major artery cuts diagonally northwest from downtown, following an old trail leading towards Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It disrupts the grid in several areas, creating irregular intersections and unique neighborhood shapes.

-

Lincoln Avenue: Another diagonal street, Lincoln Avenue, winds its way northwest, offering a picturesque, albeit less predictable, route.

-

Elston Avenue: Similar to Milwaukee and Lincoln, Elston Avenue provides a diagonal path through the northwest side of the city.

These diagonal streets, while potentially confusing for newcomers, add character and historical depth to the city’s landscape. They often become focal points for neighborhood activity, hosting vibrant commercial strips and unique local businesses.

Beyond the diagonal streets, some areas of the city, particularly those annexed later, exhibit variations from the strict grid. These deviations often reflect the pre-existing street patterns of the smaller towns and villages that eventually became part of Chicago.

The Impact of Rivers and Railroads: Obstacles and Opportunities

Chicago’s geographic location, at the confluence of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan, and its status as a major railway hub, have also shaped its street map.

-

The Chicago River: The river, once a crucial transportation artery, necessitated the construction of numerous bridges, influencing street alignments and creating occasional disruptions in the grid. The iconic movable bridges, allowing passage for both street traffic and river vessels, are a defining feature of Chicago’s urban landscape.

-

Railroads: Chicago’s prominence as a railroad center led to the construction of extensive railway lines, often bisecting neighborhoods and creating physical barriers. Viaducts and underpasses were built to maintain street connectivity, but the presence of railroads undeniably impacted the flow of traffic and the development of certain areas.

Despite these challenges, Chicago managed to integrate these features into its urban fabric. The riverfront has been transformed into a vibrant recreational space, while efforts are underway to improve the accessibility and walkability of areas affected by railroad lines.

Street Naming Conventions: History and Identity

The names of Chicago’s streets often reflect the city’s history, its prominent figures, and its diverse communities.

-

Historical Figures: Many streets are named after prominent figures in Chicago’s history, including founders, politicians, and influential citizens. Names like Clark Street (after George Rogers Clark, a Revolutionary War hero) and Dearborn Street (after General Henry Dearborn) are common reminders of the city’s past.

-

Geographical Features: Some streets are named after geographical features, such as Lake Shore Drive (following the Lake Michigan shoreline) and Ridge Avenue (following a glacial ridge).

-

Community Identity: Street names can also reflect the identity of specific neighborhoods. For example, streets in Ukrainian Village often have Ukrainian names, while those in Pilsen may have Czech or Mexican influences.

The street names of Chicago provide a valuable glimpse into the city’s rich and diverse history, offering clues about the people and events that shaped its identity.

The Grid as a Tool for Urban Planning and Social Equity

The rectilinear grid, while primarily intended for efficient transportation, also had implications for urban planning and social equity. The regular layout facilitated the subdivision of land, enabling the orderly development of neighborhoods and the provision of public services.

However, the grid also presented challenges. Its uniformity could sometimes lead to monotony and a lack of distinct neighborhood identities. Furthermore, the grid’s inherent egalitarianism could mask underlying social inequalities, as different neighborhoods developed along vastly different trajectories despite sharing a common street pattern.

Modern urban planning efforts in Chicago often focus on addressing these challenges, seeking to enhance neighborhood character, promote equitable development, and mitigate the potential negative consequences of the grid’s uniformity.

Modern Challenges and Future Adaptations

In the 21st century, Chicago’s street map faces new challenges, including increasing traffic congestion, the need for sustainable transportation options, and the integration of new technologies.

-

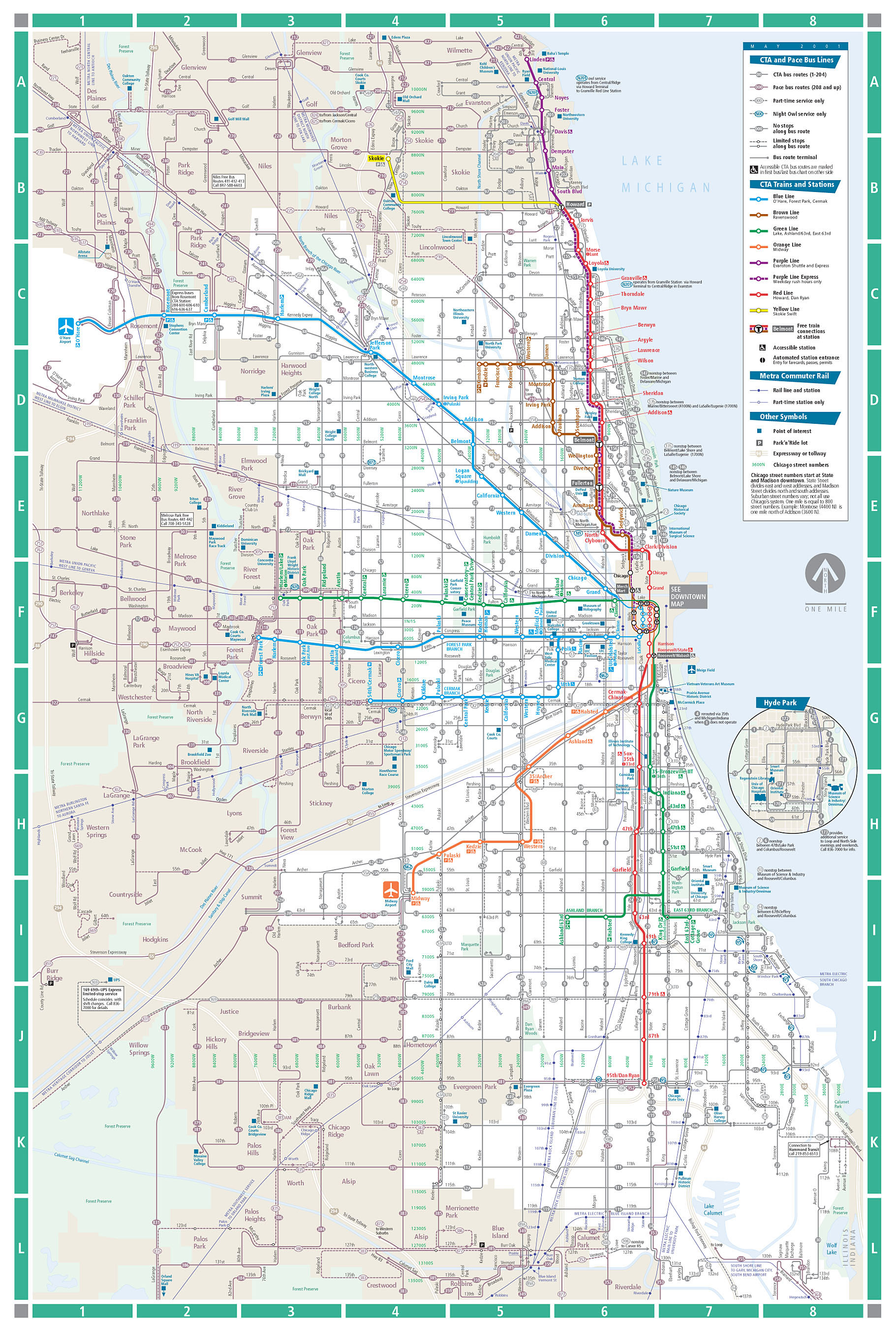

Traffic Congestion: The grid, while generally efficient, can still become congested during peak hours. The city is exploring various strategies to alleviate traffic, including improved public transportation, bike lanes, and intelligent traffic management systems.

-

Sustainable Transportation: Promoting sustainable transportation options, such as cycling and walking, is a key priority. The city has invested heavily in bike lanes and pedestrian infrastructure, aiming to create a more bike-friendly and walkable urban environment.

-

Smart City Technologies: Integrating smart city technologies, such as real-time traffic monitoring and adaptive traffic signals, can further optimize the efficiency of the street network.

Conclusion: A Living Document

Chicago’s street map is more than just a collection of lines and names; it is a living document that reflects the city’s history, its aspirations, and its ongoing evolution. The rectilinear grid, born from the Burnham Plan, provides a foundation of order and navigability, while the diagonal streets, rivers, railroads, and street naming conventions add layers of complexity and historical depth.

As Chicago continues to grow and adapt to the challenges of the 21st century, its street map will undoubtedly evolve as well. New technologies, sustainable transportation initiatives, and innovative urban planning strategies will shape the future of the city’s streetscape, ensuring that it remains a vital and dynamic component of Chicago’s urban identity. Understanding this map is understanding Chicago itself, a city of progress, innovation, and enduring resilience.

![]()